Ría, everything remembered is dear, everything remembered is there is a limited edition, bilingual (Spanish/English) artist book. The book contains 37 original prints (photo-etchings and photogravures) by artist Lihie Talmor and a road diary by media anthropologist Ruti Talmor. The diary recounts the journey mother and daughter made through Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee, following in the footsteps of a young, not yet famous Elvis Presley. The book is accompanied by an essay by writer, poet and scholar María Fernanda Palacios and a commentary about the prints by art historian Federica Palomero. Original texts in English were translated to Spanish by Sandra Caula. Original texts in Spanish were translated to English by Ruti Talmor and Pedro Leonardo González Silva. Proofreading was done by Sandra Caula and Ruti and Lihie Talmor. The edition consists of 15 copies in Arabic numerals, 3 copies in Roman numerals, and 2 unnumbered copies Hors Commerce. The photo-etching plates were created at the Gottesman Etching Center (Ofra Raif, director) in Kibbutz Cabri, Western Galilee, Israel. The photogravure plates were made at the studio of artist and master printer Lothar Osterburg in Red Hook, New York, USA. All the images of the book were printed at Osterburg’s studio on French folded double spreads (42 x 66 cm) of Hahnemühle German Etching white 310 g/m² paper. All captions were handset and printed at Arion Press in San Francisco, California, USA. Essays were printed at A.R. Print Ltd. in Tel Aviv, Israel. The book was designed by Avigail Reiner -The Studio in Tel Aviv, Israel. Bookbinding was executed at the studio of Ido Agassi in Ra’anana, Israel. The project was managed by Lihie and Ruti Talmor.

We spent thirteen days in southwest Alabama, northeast Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee. Mostly we drove down small country roads in a random, partial tracing of the thousands of miles in his shoes. In Elvis’s first year of performing, he was often in a different town every day. It would be impossible to retrace the imagined zigzag map of tread marks he and his bandmates—guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black— had made upon the landscape, driving back and forth across the South. Our strange, brief trip was similarly beautiful. Anthropologist-detectives, we followed the random networking paths laid out by people we met by chance. One person told us of the next. All welcomed us with grace and shared their stories.

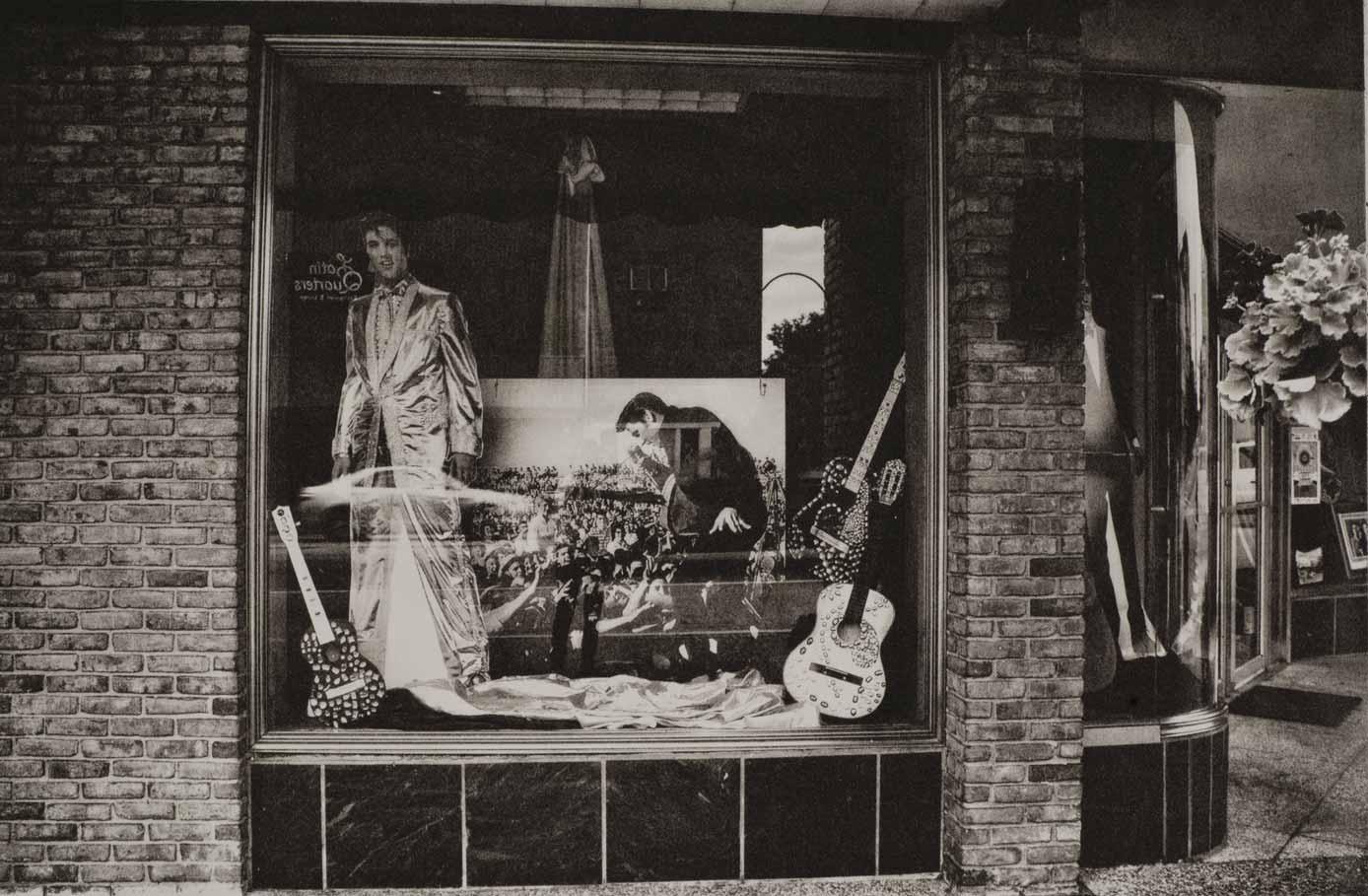

The interviews meandered just as our journey did. We always began with the encounter: How did you know Elvis? What did he mean to you? But this always led outward onto the identity of the American South, and inward into people’s understanding of themselves. We met people who knew Elvis when he was a child, a playful teen on the brink of fame, a boyfriend, a star of inconceivable fame. People’s whose lives had been dedicated to his memorialization, others who gained a modicum of fame from their proximity to him, and still others for whom he had been a blip relevant only in the retrospective meaning of his stardom.

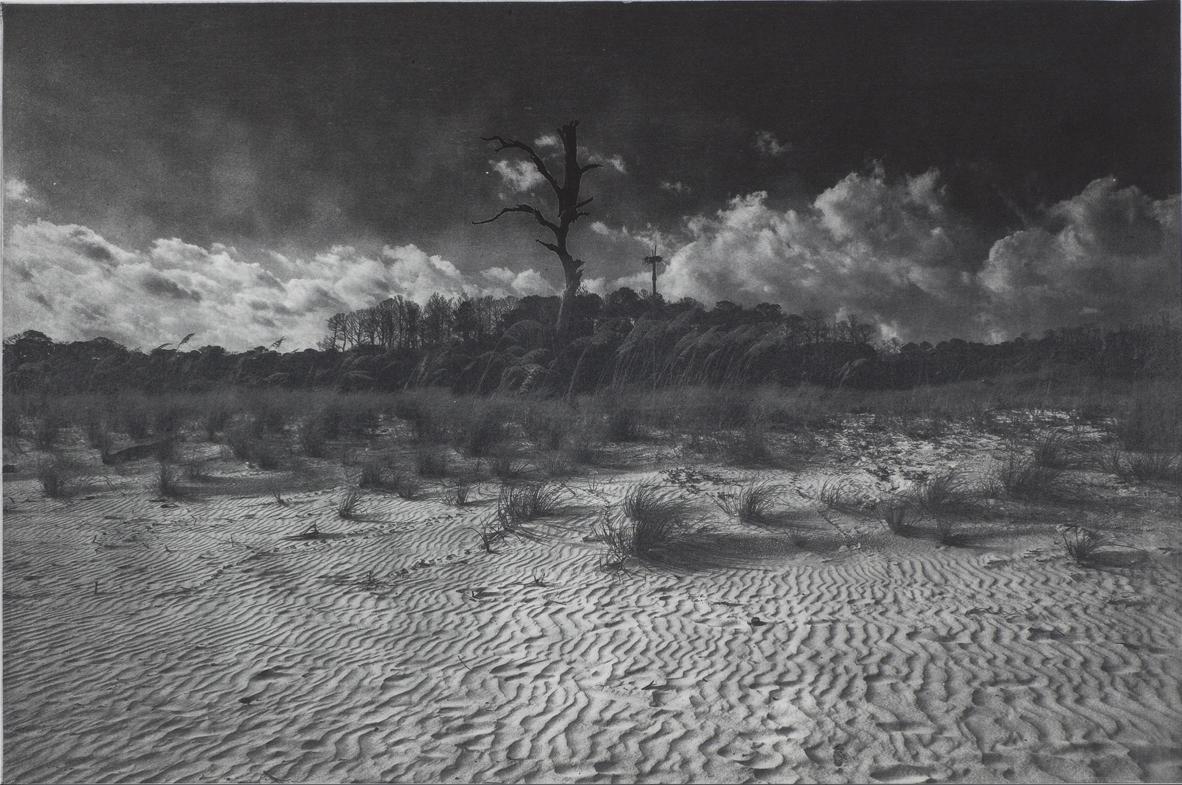

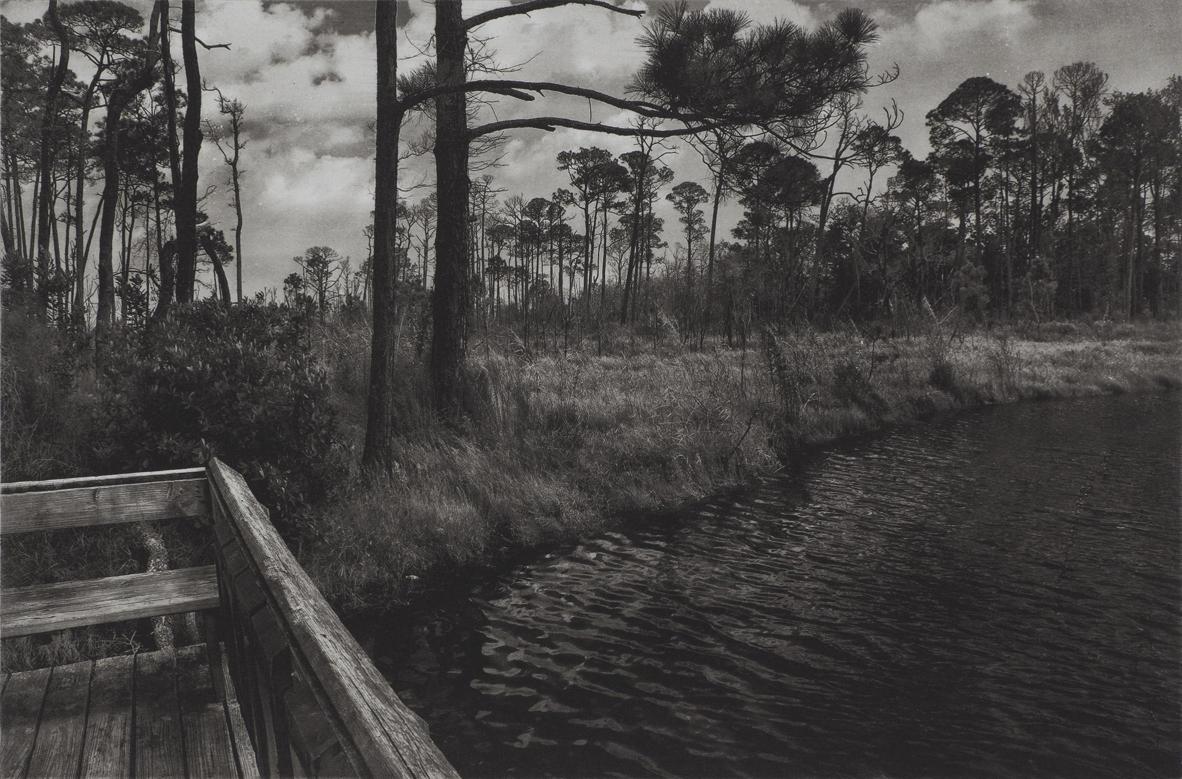

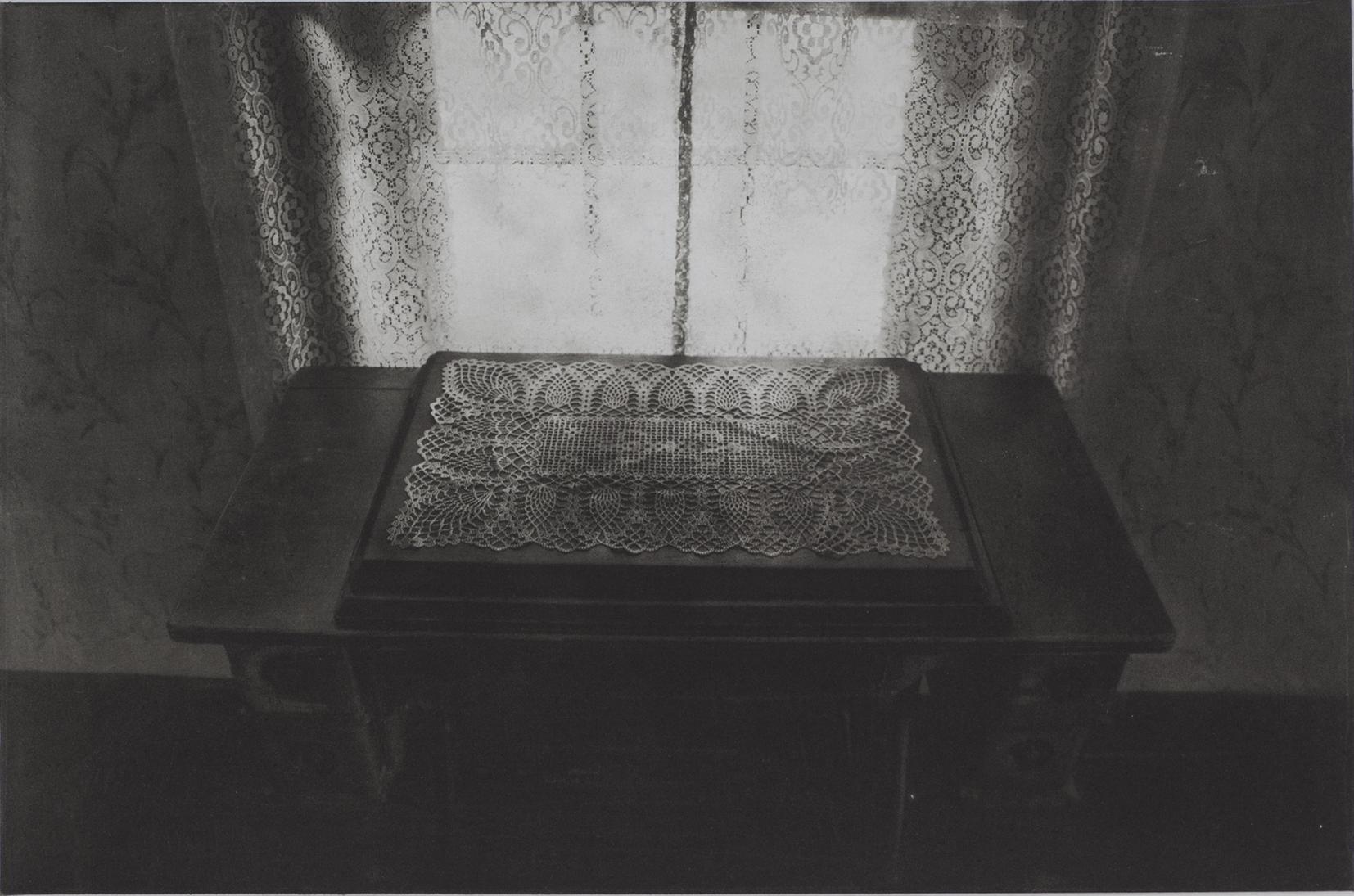

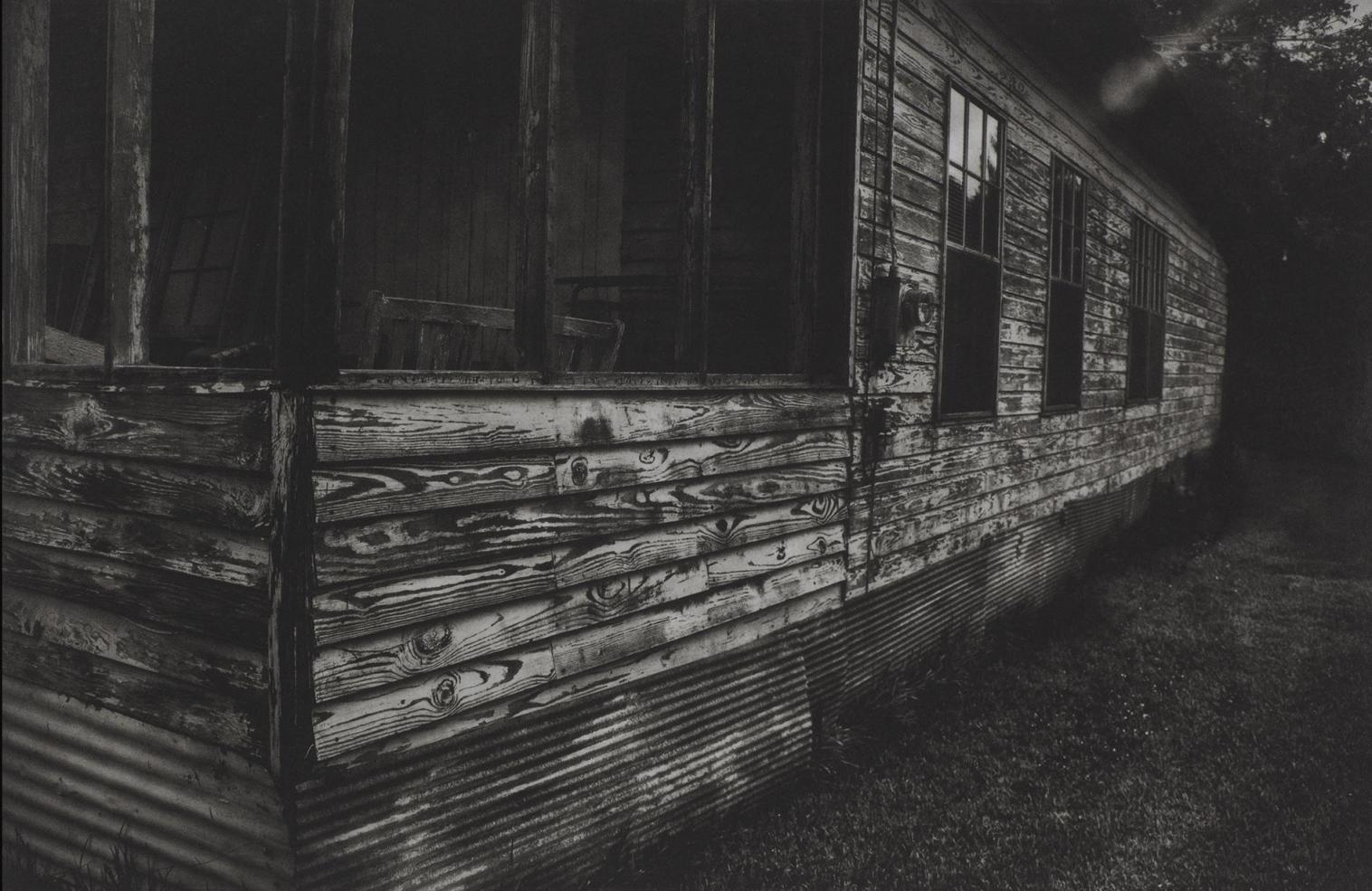

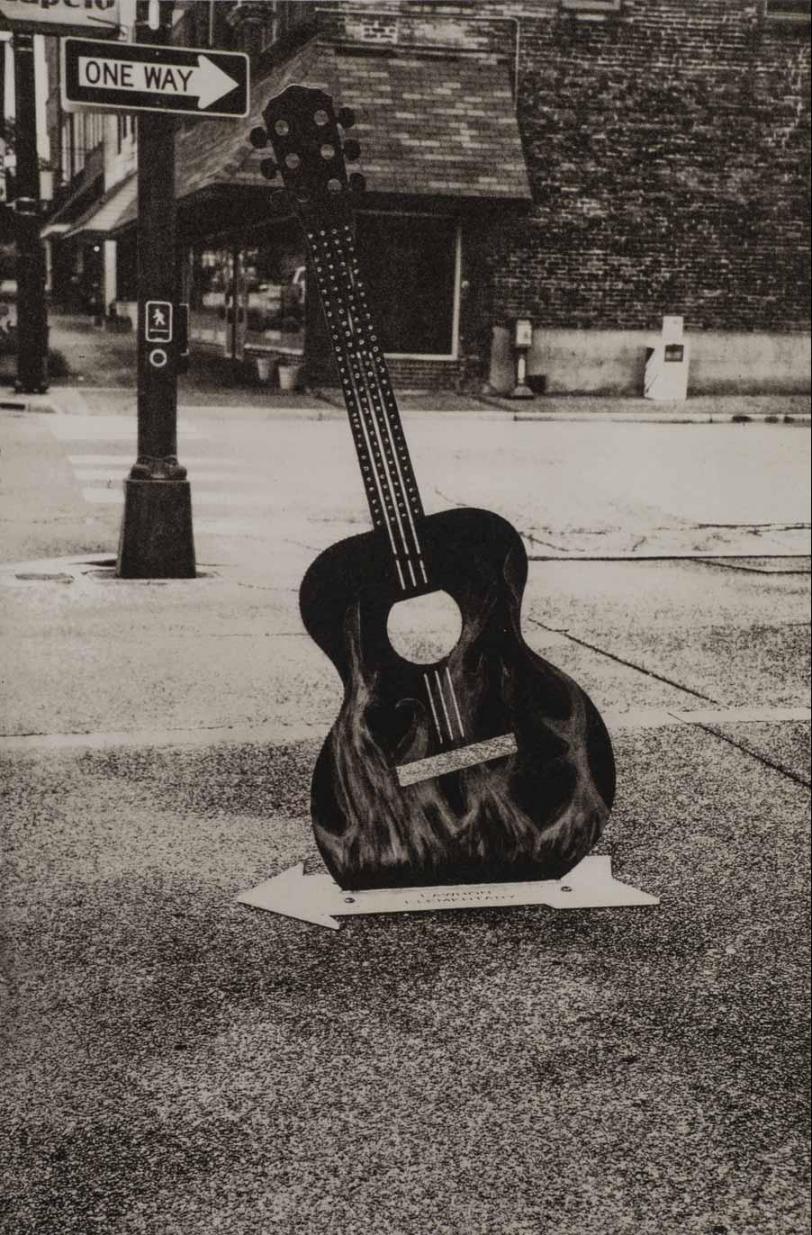

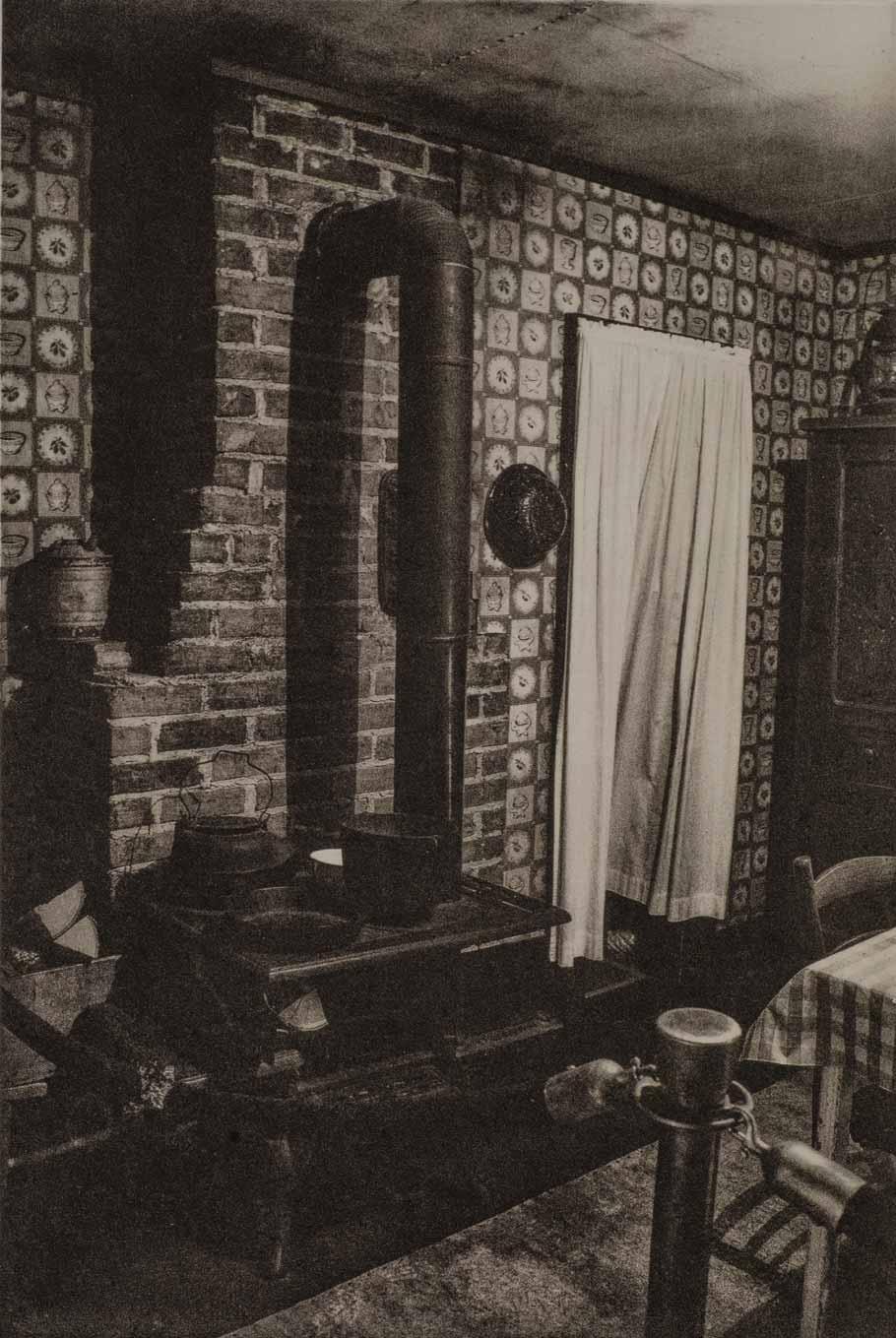

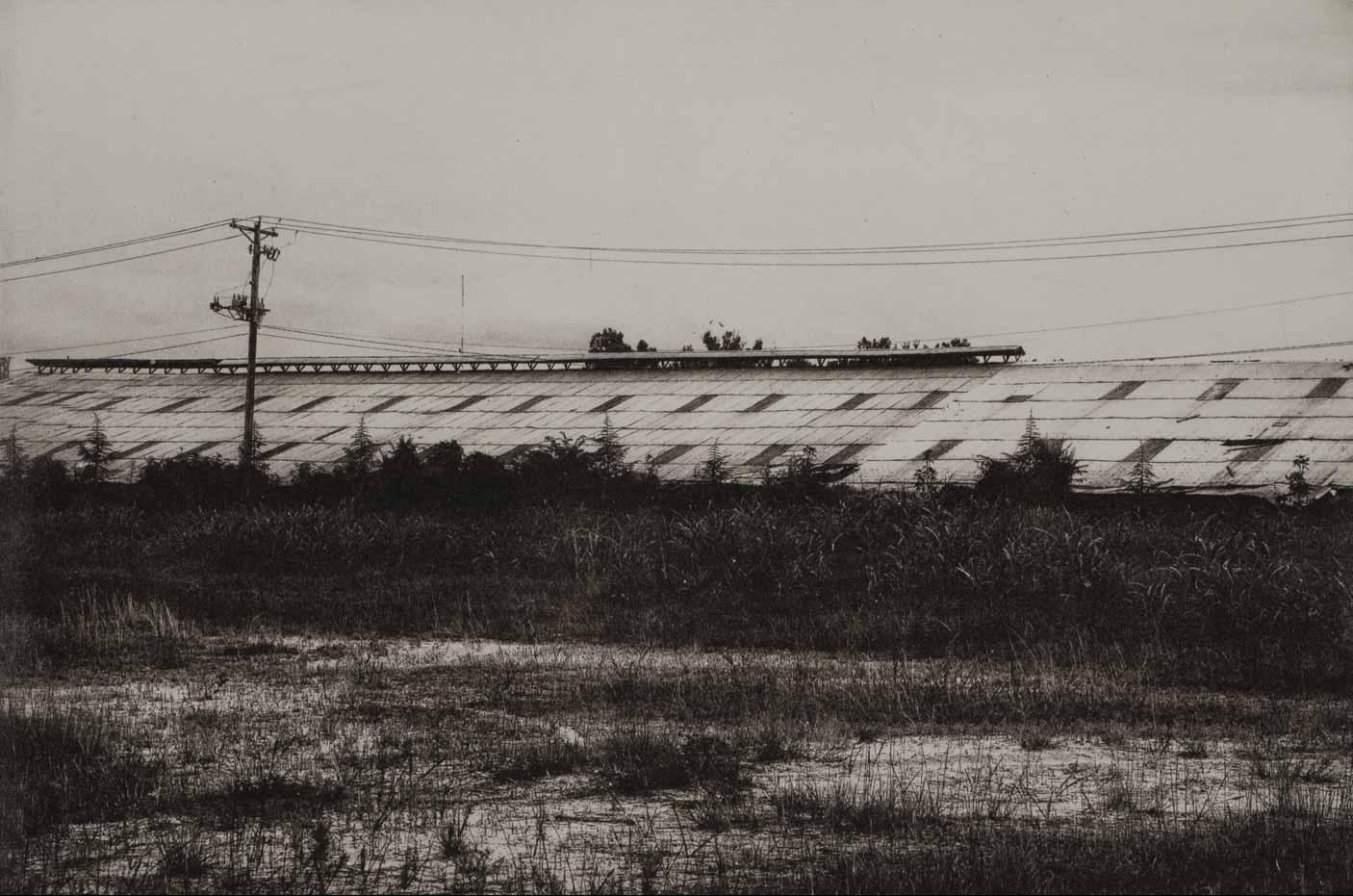

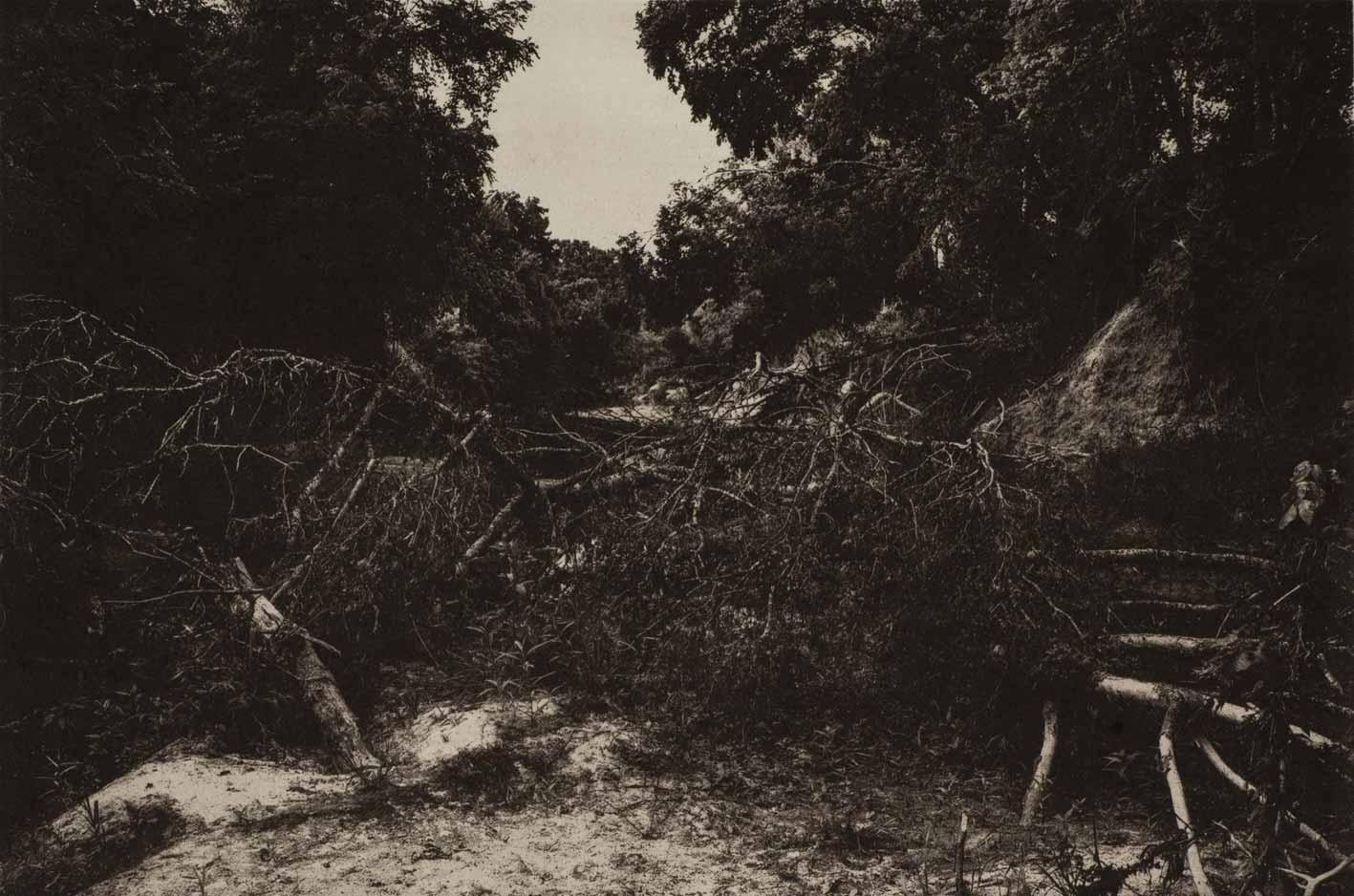

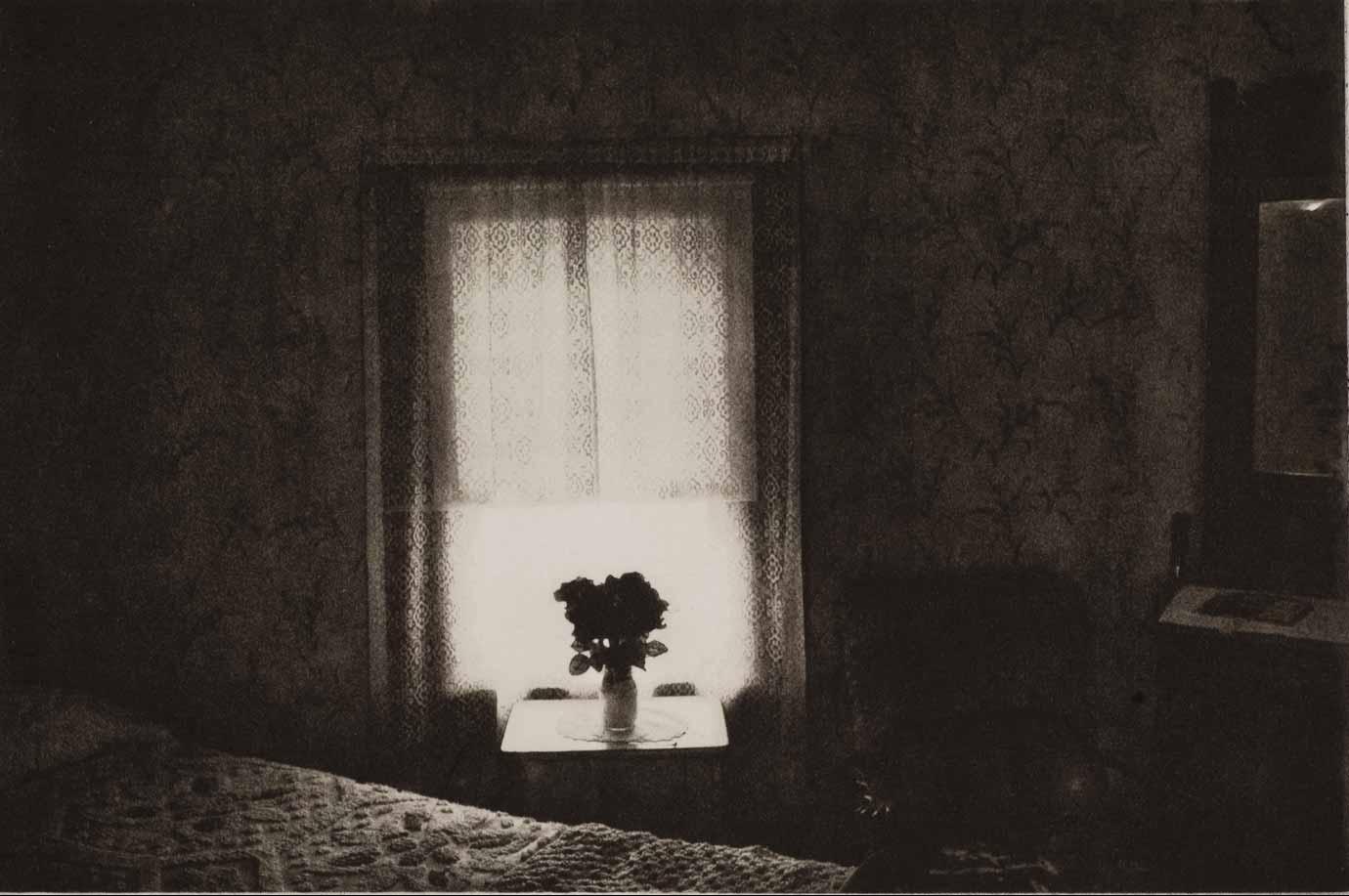

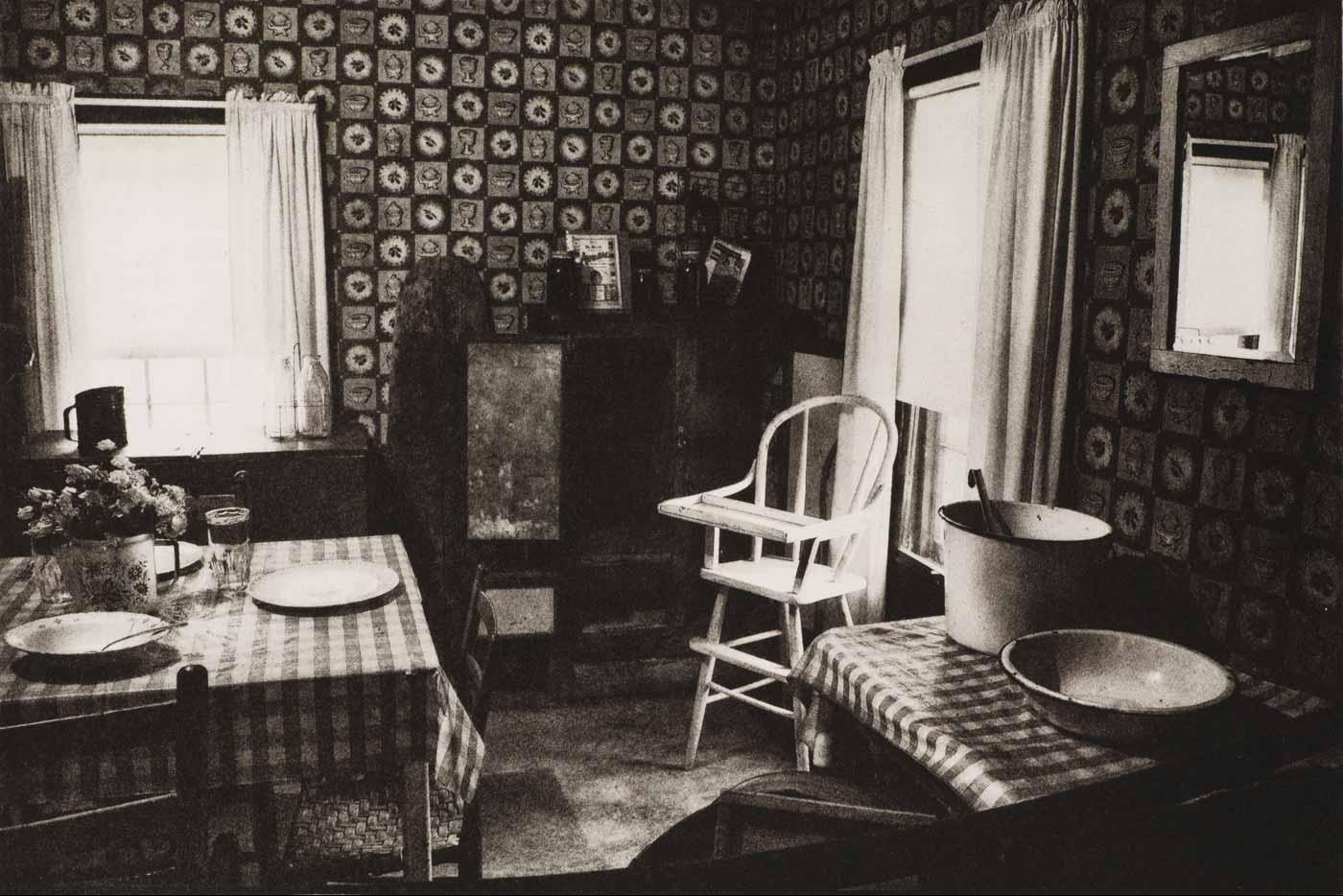

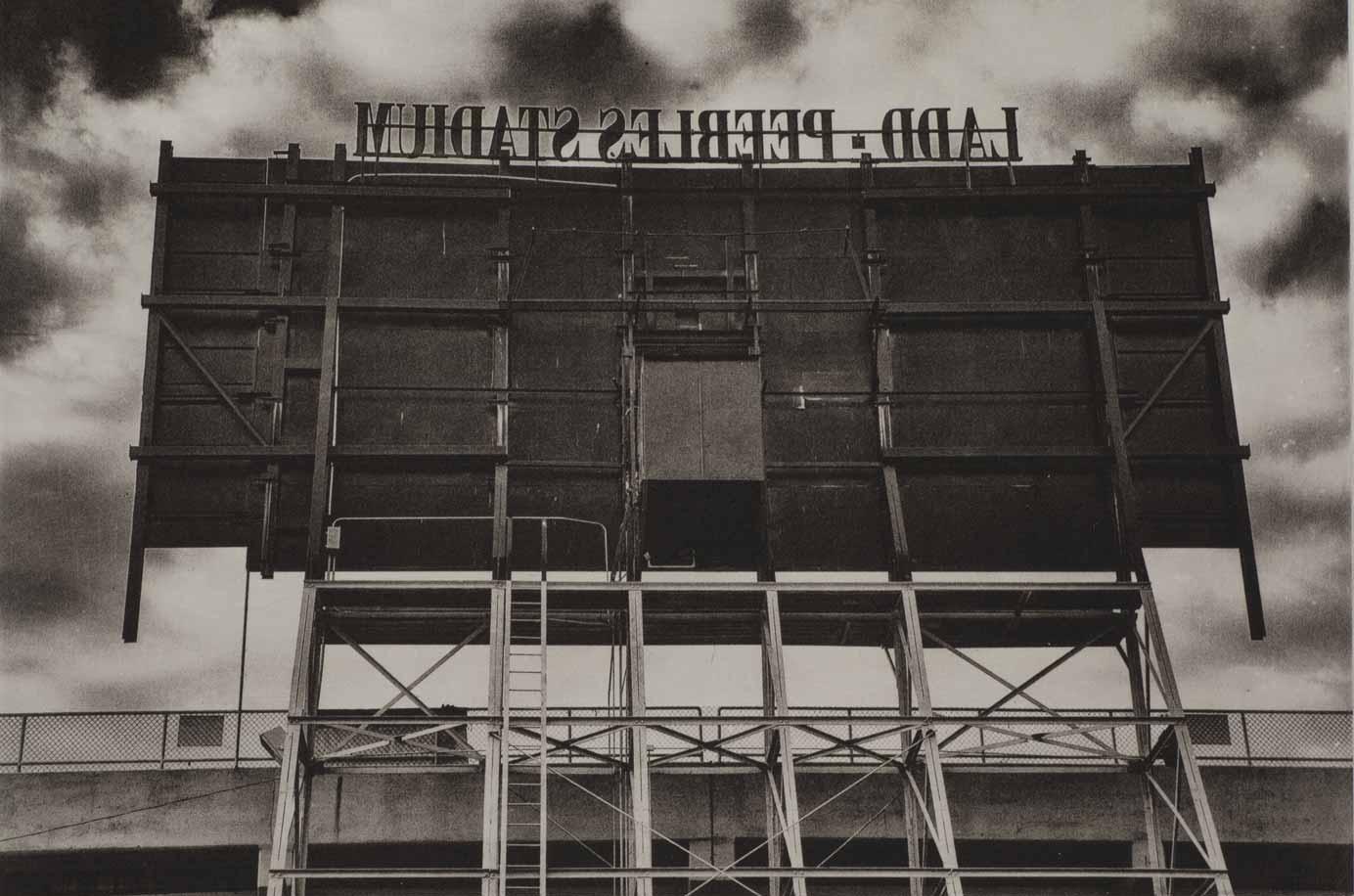

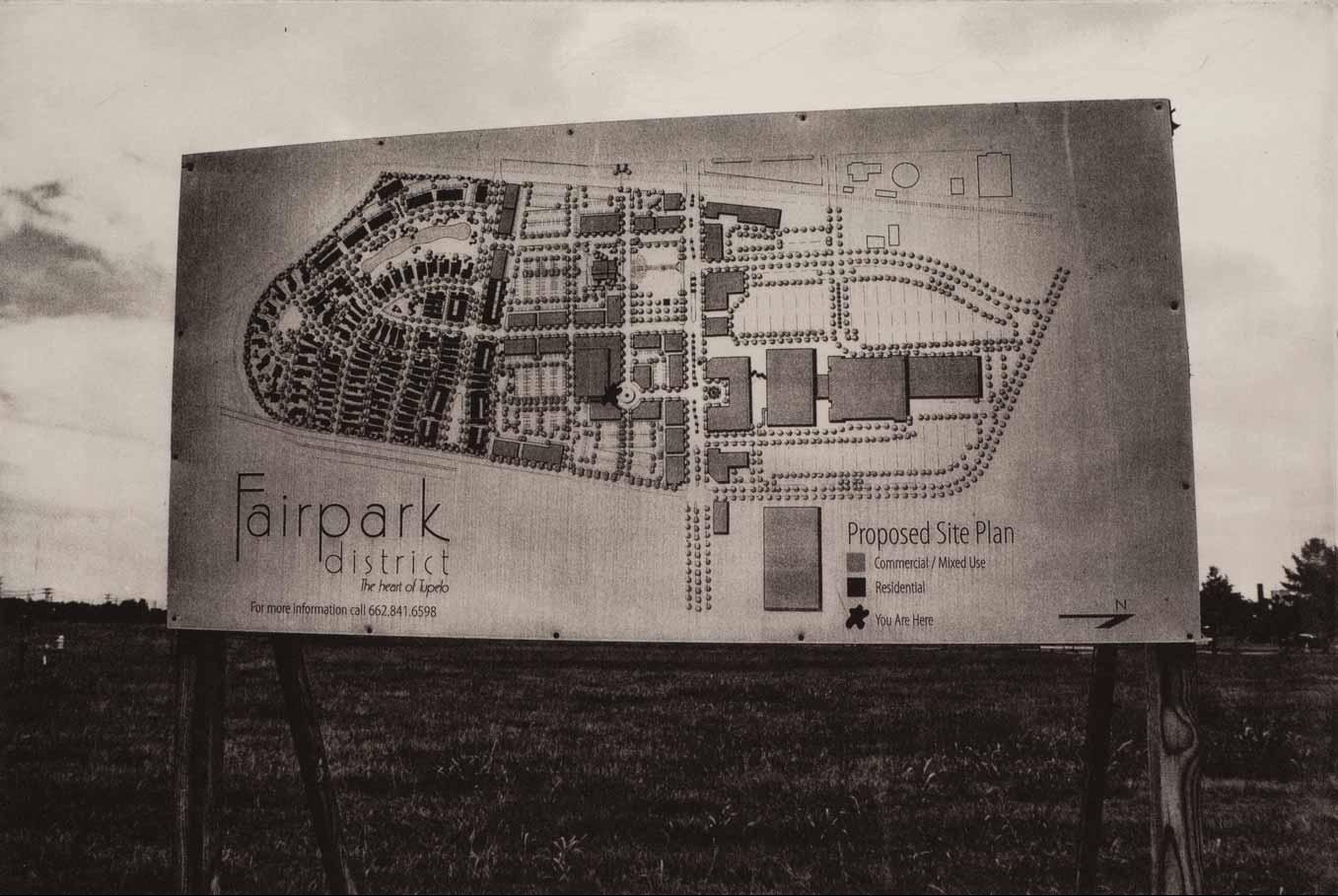

Of the 1,311 digital photographs Lihie took, 18 became large photogravures, and an additional 19 became smaller photo etchings. The “large set” of photogravures look like what we were doing and feeling: we were looking for a present-absent, trying to find traces of Elvis in places where he had once been, in people he had once known. Hence the first series—as photographs—was filled with a fulsome emptiness. As photogravures, Lihie has imbued them with haunting, longing, loss, wonder, and possibility. Something tickles at the edge of our vision; something dances deep within the stillness of the image. There are views of nothing: windows blocked by lace, abandoned structures, an empty beach, an empty lot. The “small set,” as I refer to the photo-etchings, are evidential— “That! There it is! Lo!” (Barthes, 1980, 5). They are the opposite of “the decisive moment” (Cartier-Bresson, 1952): they capture no event; they document the search.