Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

Inferred Fault

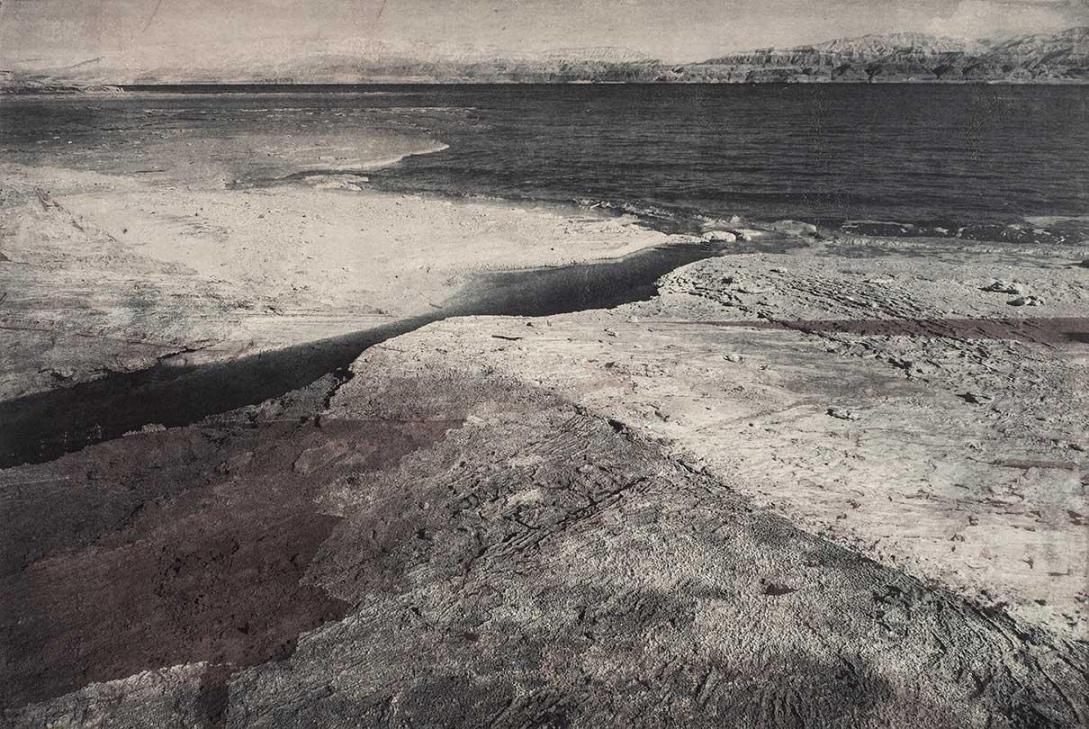

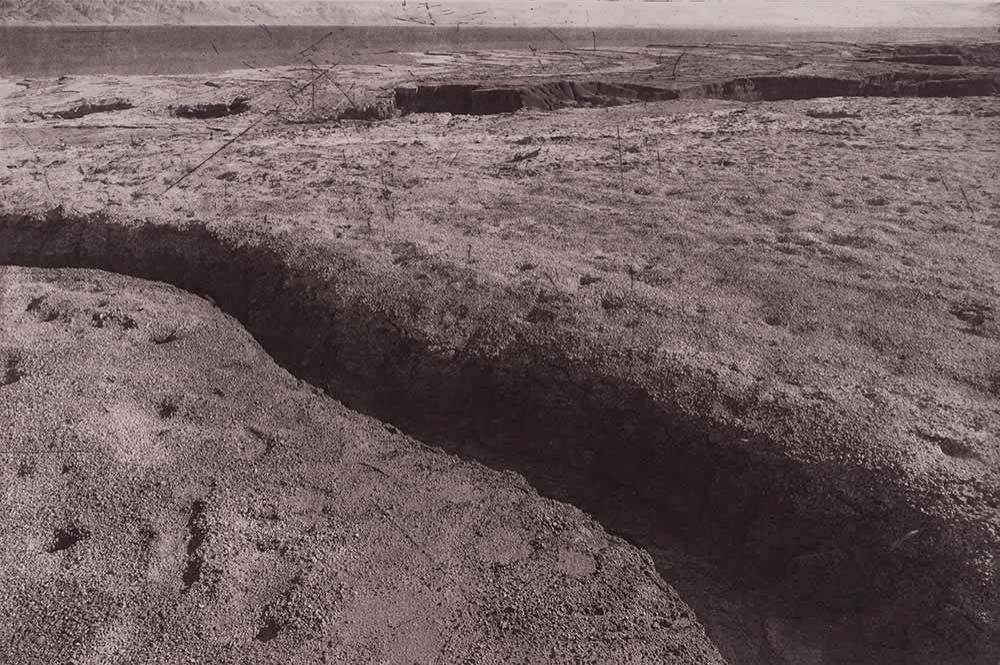

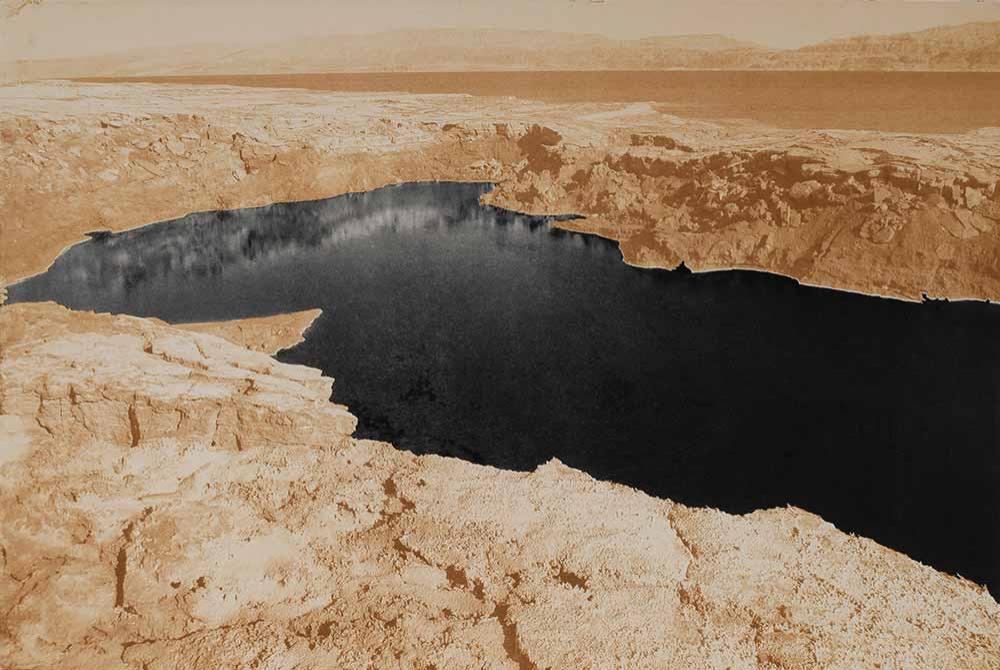

My etchings are inspired by photographs I often take at very precise moments in order to document experiences; the images become the specific, referential springboard for the development and evolution of sundry thematic series of works. Over the last few months I’ve been developing a project that is deeply meaningful to me, and although very personal, feels incredibly relevant to the current global situation, as it engages with the ecological, environmental and political significance of the proliferation of sinkholes in the Dead Seai The project has involved a great deal of research and multiple excursions (during the COVID-19 pandemic) to the Dead Sea area. Sadly, the sinkholes are a consequence of human activity, as new water-diversion systems have brought about changes in water-drainage patterns. These changes cause the ground to collapse, resulting in a sinkhole.

Inferred Fault is a series of photo-etchings made after digital photographs taken during those visits and guided excursions to the Dead Sea area, specifically the adjacencies of the Ein Gedy Kibbutz.

Mallarmé once said that a poet does not invent new words but new places for words. I am prone to believe that an artist finds new places for new images; creating metaphoric and fictional worlds anchored in space and time. Throughout the whole process of the making of the work, cultural, visual and semantic associations and connotations find their way to penetrate through the layers of the etchings in an adding and subtracting process. I explore the territory and its relationships with its past and present, keeping the past as a living memory, a refuge for remembrance.

The work and its meaning occur in stages, or rather arise from the disjunction involved. First there is the moment that leads to the taking of the photograph. This moment —an inexplicable combination of framing, angle, light and other elements— creates a feeling of accuracy and necessity that drives me to take the picture. My sensations at this moment impregnate and ultimately define the image I eventually produce through my work as an etcher. I tend to preserve the primary composition and structure of the photograph while altering the relation, morphology, texture and color of the elements that make it up, thus creating a feeling of wonder.

i Every year, hundreds of sinkholes appear along the banks of the Dead Sea, some as deep as a two-story building. Although the pockmarked landscape may look strikingly appealing in aerial photos, the sinkholes are in fact a big problem - one that will require significant human effort to remedy. Salt plays a supporting role in the sinkhole outbreak. People play a much larger one. Demand for water from the Jordan River, the main tributary of the Dead Sea, has ramped up in the last few decades, with water being siphoned off for drinking, irrigation, and industrial activity. This diversion has caused the Dead Sea to shrink rapidly, losing around three feet each year. Unfortunately, the recession of the salt water allows freshwater to flow into underground layers of earth near the shoreline. The freshwater dissolves the salt brines in these areas, creating underground cavities capable of collapsing into themselves at any moment. There’s no consistent way to predict when or where the earth will crumble. As the sinkholes continue to appear, in December 2013, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority signed on to a $900 million public works project to combat the Dead Sea’s diminishment. A new desalination plant in the Jordanian port of Aqaba, on the Red Sea, will provide fresh water for all parties, and the brine produced as a result will be transported via a 110-mile pipeline to replenish the Dead Sea. For the time being, though, watch your step.

Lihie Gendler Talmor